Agile at Scale with Flight Levels®

Flight Levels Case Study

Manfred Hellfurther had to take a deep breath. He would never have believed that his scaling project would cause such problems for him. At the beginning, the Chief Technology Officer (CTO) of a large insurance company thought he had finally found the right way to take their agile way of working to a new level. In the future, there should not only be individual Scrum and Kanban teams but the entire IT should be organized in an agile manner. But somehow, the Spotify model (see below), with which he wanted to reorganize his more than 500 experts, caused strange misunderstandings. The basic structure of the so-called squads, which were brought together vertically in business-specific tribes, the role-specific chapters and the topic-oriented guilds, was nowhere near as clear to his people as it was to him. Why should the teams suddenly reorganize? He was repeatedly asked about the reason for renaming the familiar structure of teams and departments, and why all frontend developers had to align with each other regularly, even though they were working on very different tasks. Manfred Hellfurther had never expected so much skepticism. He was, however, still convinced of his scaling plan — after all, he knew that people need time to get used to change. It was also clear to him that not all his employees had the open mindset he saw as the heart of the agile approach. To consistently promote this cultural change, he hired two Spotify experts, invested in various training courses, and extended his team of agile coaches. So, everything was done to ensure the success of his scaling project, and he just had to be patient until the whole organization was as responsive and swift as he imagined. Or maybe not?

Given the scaling initiatives that have been launched in many organizations in recent years, Manfred Hellfurther's doubts appear to us to be entirely justified. From our point of view, his experiences highlight some characteristic obstacles that repeatedly block real business agility:

- Standardized frameworks are the focus, and the current problems and strengths of the organization are secondary. This often triggers resistance among employees, as many have the feeling that their current work situation is as little noticed as the successes that have been achieved so far. Instead, a normative model is imposed on them, the benefits of which often remain unclear.

- Organizational change is pushed by top management, planned by external scaling experts, and rolled out using traditional project management tools. Subject matter experts as well as middle managers are only involved in the change to the extent that they are supposed to properly implement ready-made solutions.

- An enormous amount of effort is required to follow the respective scaling approach. Comprehensive training, team workshops, and management coaching, let alone the certification costs that arise for using a specific framework. Possible side effects of large-scale initiatives on productivity or morale are not considered.

- Measurable improvement only occurs when everything has been implemented according to plan. This means that although a lot of investment has to be made at all levels, the return from the scaling initiative depends on everything working in practice as intended in theory.

Since the appetite for business agility has increased significantly in recent years, several other scaling approaches have been established in addition to the Spotify model. Particularly noteworthy here are the Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe - see below) and the Large Scale Scrum framework (LeSS - see below). In practice, however, these approaches entail similar difficulties as those highlighted above. Nicole Barth, Managing Director of a large IT Services provider, for example, began transforming the entire company to SAFe in 2021. However, the better outcomes she expected by establishing business agility have not yet materialized. After two years of countless consultations, leadership workshops, and role training, the delivery times of their products have neither been significantly shortened nor their quality improved. The so-called Agile Release Train, through which complex development work is bundled in SAFe, tends to make a name for itself due to delays; key players such as the release train engineer, the product owners, and the agile coaches are still poorly coordinated; and the last big room planning, in which all 120 IT specialists were supposed to take part, as usual, was pretty chaotic from Nicole Barth's point of view. The whole story is crowned by the last employee survey, which confirmed what Ms. Barth had noticed more and more recently: employee satisfaction and motivation levels have decreased dramatically!

Strict guidelines instead of meaningful participation, expert dictates instead of co-creation, complicated roadmaps instead of a lean approach: Anyone who follows this “recipe” need not be surprised by negative feedback. Leonie Dellago experienced something similar in her role as Head of Digitalization in a large infrastructure company. Because as much as she was convinced that her software development teams needed to coordinate themselves more regularly, manage their technical dependencies more proactively, and solve cross-team problems more quickly, after five months of change dynamics, she had to admit that the Large Scale Scrum framework (LeSS - see box) did not fit the needs of her organization. In the beginning, she consistently implemented all the suggestions put forward by the LeSS consultants and also defied the skepticism of some of her key players. Even though she also had invested heavily in training and repeated her explanations of “Why LeSS ?” like a mantra, the message didn’t seem to be getting through to people. Or why else was the interaction of their Scrum teams still rather bumpy? The Scrum-of-Scrum meetings did not have the expected coordination effect and the role of the Area Product Owner did not encourage significant improvements.

So, do initiatives to scale agile share the same logic of failure that has characterized so many change projects in recent years? Should we say goodbye to the idea of business agility? Although we claim that the three short case studies illustrate some patterns that we have discovered in numerous other organizations, we do not want to bury the idea of enterprise-wide agility. On the contrary, the Flight Levels® approach (see below) shows that there is another way.

- Instead of starting with standardized solutions, Flight Levels first focus on the problem. More precisely, the current challenges that an organization is facing, but also the successes, strengths, and resources on which it can build. Clarifying conversations with a wide range of specialists and managers help to explore the current situation and the specific need for improvement.

- Flight Levels initiatives are also mandated by senior management. However, this doesn't necessarily mean that change is pushed top-down in the traditional way. Rather, management acts as an active sponsor of improvement and models the co-creative engagement that is at the heart of Flight Levels change. External coaches, therefore, do not dictate but rather inspire and facilitate the journey to business agility.

- Such a journey does neither require extensive training regimes nor complicated roadmaps. The lightweight model of Flight Levels is accompanied by an evolutionary approach that focuses on manageable iterations of change, learning by doing, and regular feedback loops.

- This agile approach means that improvements can be made not just at the end of the organizational journey but at every stage. This means that the start-up phase, i.e., the professional preparation, design, and testing of Flight Levels systems, can be kept well on track. For operation, all you need is a design that is good enough, as this is continuously being improved.

- Last but not least, the Flight Levels focus on the pulse of the respective business activities. The operational structures and value creation processes are made visible and improved in a goal-oriented manner. This does neither require new roles like in SAFe or LeSS nor a complex change in the organizational structure à la Spotify.

Above all, what sets Flight Levels apart from all other scaling approaches is their change philosophy. “If the goal is agile, the way to get there should also be agile,” this philosophy could be summed up in a nutshell. The case study of a media company with over 3,000 employees shows what this can look like in practice.

This company's journey of change started with strong feelings: the confusion of many media business people due to rapid digitalization and AI; customer dissatisfaction over error-prone product features and poor service; the digital experts’ complaints about their overburdening workload; the digital managers´ uncertainty as to why their agile teams were performing poorly. When Harald Girol, the company's Chief Technical Officer (CTO), contacted us, there was massive frustration in the air. Nevertheless, it didn't take long for us to agree on initial support steps. We arranged a series of short meetings in which we, together with the CTO and the Head of Product Development, explored some root causes of the current problems and clarified the most important cornerstones of organizational improvement. From the point of view of the two managers, what exactly should be improved? Why did they think such an improvement was important? Who should be involved, and in what form? How should the change approach look like in order to realize the desired improvements?

In parallel to the intensive sparring that took place in the following weeks, we conducted interviews with key players from a wide variety of organizational units. These conversations were intended to provide additional insights about the current situation but also to signal that the input from our interviewees was guiding further action. Ultimately, Flight Levels change does not start with a ready-made solution but with the key business challenges that specialists and managers agree on. We visualized and clustered the most important answers from the interviews in a way showed the media company's strengths as well as its problems and areas for improvement. Together with our sponsors, we translated these answers into what we call the north star of improvement in the tradition of lean management. “Faster added value” was this north star, which addressed the business problems most frequently mentioned in the interviews: long cycle times, poor product quality, and customer dissatisfaction. These problems were primarily attributed to three root causes: firstly, unclear work processes; secondly, the lack of coordination between the individual teams; and thirdly, the diffuse corporate strategy.

All three causes suggested an agile scaling initiative and the idea of designing this initiative using the Flight Levels model. On the one hand, we wanted to co-create a Flight Level 2 system to ensure better coordination between all teams involved in product development — end-to-end, i.e., from the first business ideas to product management, user experience, data and development to the customers who used the delivered product. On the other hand, we saw the need for a Flight Levels 3 system in order to better align the entire product development with the corporate strategy.

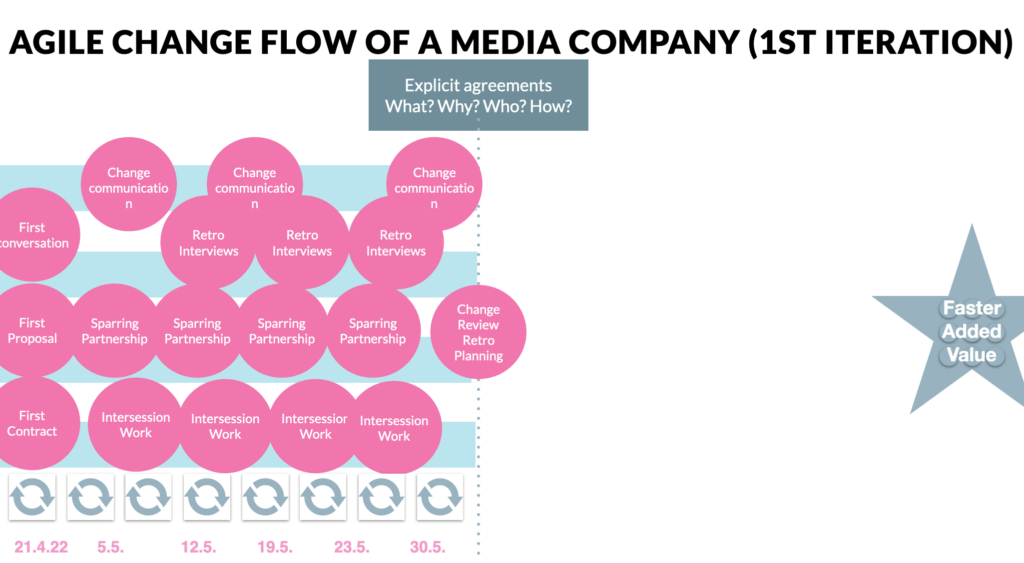

Following our motto of an agile journey to business agility, we suggested to our two sponsors that we proceed in manageable iterations with clear outcomes. What was important was that we only defined the expected outcomes more precisely for the next 2-6 weeks. For each of these iterations, agreed on the specific change formats, i.e. the flow of meetings, workshops, bilateral conversations, and intersessions we would use to achieve the expected outcomes. At the end of each iteration, we reflected on what we had actually achieved, how our collaboration had gone, and what conclusions we could draw from this for our next iteration.

The north star gave the media company's Flight Levels initiative meaning and direction, the iterative approach allowed us to break this initiative down into outcome-oriented stages, the change formats fostered employee engagement, and the feedback loops ensured continuous learning. In the first iteration, we worked primarily with the sponsors to achieve explicit agreements on their improvement initiative. We agreed on the agile approach and clarified how the Flight Levels model could support us. In the second iteration, we expanded our guiding coalition by building a dedicated change team. This cross-functional and hierarchy-bridging group of 8 people from different departments, the Head of Product Development and one of us coaches, was responsible for the overall change flow, facilitated the various change formats we used for, and took care of the ongoing change communication.

This means that we as Flight Levels experts were still there to provide guidance and support. The decisions about iterations, expected outcomes, and specific interactions were made together according to the consent principle. This meant that the organization itself took full responsibility for improving step by step rather than implementing a set of predetermined roles, processes, and artifacts as with other scaling approaches. Together with the sponsors, the change team also decided to focus on broader communication by sharing the initial interview results with all employees, inviting the two sponsors to a panel discussion, and providing information about business agility in informal brown bag and happy hour meetings. In addition, the change team prepared for a large group workshop to introduce Flight Levels to a broad variety of business and IT people. With this 6-hour format, in which a total of 120 product development experts and stakeholders took part, we invited everyone to start with their current situation, identify the most important strengths and problems across all teams, and prioritize the areas for improvement. After this kind of retrospective, we introduced the Flight Levels model and used an experiential activity to explore key aspects such as flow, work in process and cycle times in an engaging and fun way. We connected the debrief of individual experiences with some more insights into Flight Levels practices and use cases. At the end the small groups built at the beginning of the workshop were invited to connect the strengths and challenges they have identified with their insights from the workshop. How did what they have learned fit into the current situation? What exactly could the Flight Levels help with? Which elements could be used for addressing which challenge? Fitness is documented by all groups recording their most important answers on stickies and assigning them to the appropriate challenges. Before the workshop was closed down, both sponsors and change team members thanked everyone for their commitment, provided information about the next steps, and invited them to a final feedback loop on the workshop.

The high investment of the change team in preparing the workshop and engaging with their colleagues was rewarded with a lot of positive feedback. Although some questions remained unanswered and some employees were still skeptical, the vast majority found the improvement initiative to be important and viewed the Flight Levels as a convincing approach. In addition, the workshop was lightweight and fun, so we achieved a spirit of optimism at the end.

This spirit remained just as trend-setting as the agile approach. In the next iteration, systemic improvement seemed to be on everyone's agenda. In addition, many employees were very willing to deal with Flight Levels even more intensively and to co-create an initial system — which in turn happened in a group of "designers,” which included four change team members but also seven experts from various teams and business areas. In contrast to big bang scaling methods such as SAFe or LeSS, not everyone needed time-consuming and cost-intensive training in Flight Levels. Learning by Doing once again led the way and ensured that just five weeks after the introductory workshop, there was a first draft system design to be shared by the designers. In order to communicate this draft as well as possible and at the same time ensure participation beyond the 11-member design group, we invited people to a so-called sounding board. In this change format that lasted three hours and included 36 people, the Flight Levels system design was presented, reviewed in more detail in small groups, and clarified to such an extent that in the end, a clear decision could be made: Yes, this system is good enough to be used in daily operation! Despite further ideas for improvement, none of the 36 participants raised a serious objection that would have prevented this official take-off.

Of course, getting used to the new ways of operating product development with Flight Levels took time and patience. At the end of the first operational iteration, however, the review of the expected outcomes was positive. Process clarity had improved, as had cross-functional and hierarchy-bridging collaboration — both of which were initially identified as serious pain points. After the next iteration, in which the focus was on promoting measurability, the first sprouts of shorter cycle time and more positive feedback from customers could actually be seen. The fact that these sprouts subsequently grew impressively confirmed the success of the scaling initiative. Improvement was certainly possible, and it not only delivered more value to customers but also created more meaningful work, and new motivation. It's no wonder that the media company ventured into the next business agility initiative almost a year later and, after optimizing end-to-end coordination with a Flight Level 2 system, started to improve the corporate strategy with a Flight Level 3 system. We'll be happy to report on that another time.

Scaling Agile with Flight Levels - How to make it happen

When implementing Flight Levels initiatives in recent years, we have learned one thing above all: If organizations want to realize business agility, the path to get there should also be designed in an agile way. Below are some good practices that have proven successful in shaping the change process.

Start with what you do now

Don’t immediately jump to solutions. Even if you find standardized frameworks appealing, it pays off to explore your current situation first. Otherwise you take the risk that your preferred solutions do not resonate with your current strengths and challenges — let alone with your employees´ point of view.

Engage people

Do not rely on expert´s analysis only. Involve both your subject matter experts and your leaders in identifying your organizational whereabouts. Trust them to come up with the biggest assets and pain points they see in their daily business and consolidate the different points of view.

Create focus for improvement

Since scaling agile is far too complex to be able to determine upfront all actions needed for organizational improvement, we just want to clarify what we want to achieve. A minimum viable North Star is all we need to focus our efforts and give a sense of direction.

Apply an agile approach

Do not roll out the classic transformation plan with comprehensive training and coaching. Instead, define manageable iterations lasting between two and eight weeks, each of which focuses on expected outcomes and ends with a self-critical feedback loop: How well did we achieve the set outcomes? How well did we work together on this? What conclusions do we draw from this for our next iteration?

Share leadership

Resist the temptation to roll-out business agility in a top-down, big bang and expert driven manner. Rather, distribute responsibility and decision-making authority wisely, building on a guiding coalition of engaged sponsors from management, a dedicated change team taking care of facilitating the whole improvement process, and a network of change agents who serve as multipliers and ambassadors.

Expect a long-distance run with detours

Business agility is a challenge for everyone. It demands regular inspection and adaption as well as continuous learning. Even an agile approach with short iterations often does not fit current needs from the market and/or from the workforce.

Authors: Siegfried Kaltenecker & Sabine Eybl

Success Stories

Real Companies, Real Results

Discover how businesses of various sizes and industries worldwide have used Flight Levels to break down silos, align teams, and drive measurable success.

Find your Starting Point for Real Impact

Start for free with the Flight Levels® Kick-Start

Kick-Start

In this free self-paced online course we discover three major topics. In less than one hour you will find out, how Flight Levels can help you and your organization in a real-word environment. This course is not only suitable for Agile Coaches, Team-Leads, Scrum Master or Change agents, but also for anyone who is curious about Flight Levels.